The Conventional Laffer Curve argument says that if income tax rates are lowered then, paradoxically (because of increased economic activity), the amount of revenue will be increased. This is presented by anti tax people as absolute and independent of what the rates are. It is frequently accompanied by a reference to the Kennedy tax cuts of the mid sixties and the Reagan tax cuts of the early eighties. It is stated that both worked. For a certain class of people two examples are enough to draw a general conclusion. The conclusion is then drawn that a tax rate cut from any rate will also increase revenue. The corollary is that a return from the lower Bush rates to the higher Clinton rates would actually reduce revenue. To see that the general argument is not valid, consider the impact on revenues of reducing the rate from 1% to 0%. Does anyone really believe that that would increase revenue?

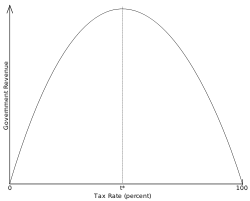

Therefore there is a problem with this argument. To see when it works and when it doesn't work, take a look at the "Laffer curve" which looks like the Gateway Arch of St Louis. You can see a larger version and discussion here . (rates below refer to the highest marginal rate)

The Valid Laffer Curve argument is this: At lower rates an increase in rates will produce an increase in revenues, but if you are on the high rate side of the maximum revenue point, then you can only increase revenue by (surprisingly) lowering the rate. After doing thought experiments considering extreme rates of 100% and 0% the basic idea is credible. (Imagine changes from 100% to 90% or from 0% to 10%.)

So when does it work? Well it depends on which side of the curve you are on. OK what is the “break point” - t* - the rate that will give you the high point (= maximum revenue) on the curve? A general answer for that question would be very hard to get. (Although the picture looks like it there is no reason to believe that it is 50%.) But we can say something about it. Let’s look at when the theory worked and when it didn’t. Kennedy’s rate drop was from 91% to 77%. Reagan’s rate drop was from 70% to 50%. Both of these produced increases in revenue, so clearly rates of 91% and 70% are on the high side of the curve. But Clinton raised taxes up to 39.5% and increased revenue. We actually had budget surpluses. Therefore 39.6% must be on the left side of the curve. This was reconfirmed when Bush lowered the rates back to 35% and revenue fell.

Therefore, the argument (lower rates produce higher revenues) works in our economy if the rates are at 70% and above and it doesn’t work if the rates are at 39.6% and below. In between we need more data.

The main conclusion is that it didn't work for Bush's tax cut.

.

Friday, August 19, 2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Thanks YA. I think I'll use this example the next time I teach optimization in any mathematics class, as an illustration of the informative nature and of the limitations of mathematical models.

ReplyDeleteOf course, anti-tax-ists (like tea partiers?) aren't interested in maximizing revenue. Instead, as I understand it, they want to "shrink government to a size where they can drown it in a bathtub" (quote attributed to Grover Norquist).

This applies in the private sector as well.

ReplyDeleteIf I price my goods or services to high too few buy my products and I go out of business. If I price my goods too low I don’t make enough profit on each item to stay in business.

Between the two extremes is the sweet spot where a business can price goods near the top end of the sweet spot (think Saks)and make a relatively large profit on each item or the business can price its goods near the low end of the sweet spot (think WalMart) making less on each sale but more profit by volume.

As YA points out there is a point where taxes rates are below the sweet spot which in the private sector would be the equivalent of a merchant who is losing money on each sale trying to make it up on volume.